The Vacant Space Inside Me

On the emptiness that develops from the completion of a novel

It’s September 2025. After a long, dry summer, the air is crisp and holds the promise of a seasonal cleansing. I want to put this note here, now, to mark this moment. It’s one of those rare, exquisite moments that are the sort I live for—and write for—although I have to be conscious about stopping to notice it; I have to pause to inhabit it as fully as I can. I’ve recently finished a new novel. Of course the novel itself doesn’t feel particularly new to me, since I’ve been living with it for the last four years, but its completion only two weeks ago does mean that its nature as a holistic piece of work is new. And, for sure, there’s a new feeling that comes with describing the work as “finished.” Despite the fortnight I’ve spent sitting with it and mulling it over—and feeling out the dimensions of the emptiness that occupies the vacant space inside me where the work-in-progress used to be—I haven’t dared call it “finished” until just now, at the very instant I reached the end of the previous sentence.

I’ve been here before, I realise. I was last here, in this state, in a moment much like this one, seven years ago, when I finished the first full draft of the manuscript that would become At the Edge of the Solid World. But, looking back through my online archives, I see that I didn’t mark the occasion. I wrote about the beginnings of that novel and reaching the halfway point, as well as various issues I encountered while I was working on it: my entanglements with narratorial voice, the embodied experience of writing a long piece of prose, the process of intuitively evaluating creative decisions on-the-fly, and the aesthetic and ethical responsibilities of feeling out the novel’s form. And then, some years after those ruminations, I wrote about my view of the novel as it approached the point of publication. I remember where I was at the moment I felt the same internal vacancy as the one I’m feeling now. In the midst of mild July in Blairgowrie, I was deep in a pine plantation, on a trail flanked by purple foxgloves. But at this point, I can only wish I’d been more attentive back then and made note of how the feeling hit me.

As for the new novel, the working title is The Burning: hence the flames. It’s not under contract anywhere and may never see the light of day. It runs the risk of flat-out failing to reach a reading public. I wrote it in full awareness of this fact, in spite of the risk—to spite the risk—and in sheer hope that when I reached the end of the writing I’d still feel that it was worthwhile even if my words wouldn’t be taken in by other eyes than mine. On that last score, at least, I’m satisfied: I look at the result of my labours and I see that the world I inhabit is a better world than the one I began from, simply for the fact that this work of art is now in it. That said, I’m aware that the qualities of the work increase the risk of its going no further. The Burning is a substantial novel. The manuscript runs to 818 pages. Some of those pages contain only images, but their deletion wouldn’t slim the total too much. The text comes out at something like 280,000 words. I have to own it: this novel is long.

The point of writing a pitch for a book is to make the concept of it saleable. The process of writing a pitch involves condensing the “aboutness” of the book into a couple of lines or a paragraph. I’ve never been able to grasp either the process or the point, but in sending the manuscript to its first reader—as nobody else has read it yet—I’ve done my best at simplification. The Burning, I’ve written in my email, “could be seen very, very generally as a work of historical fiction and a Künstlerroman. Its central figure is the Australian painter John Peter Russell, who left Sydney for London in 1880, in his early twenties, and then moved to France. Russell eventually settled on a remote island, Belle-Île-en-Mer, off the coast of Brittany, where he saw out the end of the nineteenth century. His life happened to be defined, and perhaps even distorted, by a series of chance meetings during this time—freakish, cosmically improbable encounters—and at the heart of the novel are the relationships and complications that developed from these.”

As far as summaries go, that seems fair. But because it’s a summary, it also seems insufficient. It leaves the reader to wonder who Russell’s relationships and complications were with. It doesn’t account for why, if The Burning is a work of historical fiction and a Künstlerroman, it is only “very, very generally so,” rather than a definitive entry into either or both of those genres. The summary doesn’t satisfy; its very being begs for something more. The novel itself is that something more, so anything more I can offer at this stage has to be just a lengthier summary—and therefore, I guess, not a pitch.

Around Easter in 2022, when I spoke to Ben Lindner on Beyond the Zero, I said this about the novel I’d been writing for the past five or six months:

I’m working on something which—if it ends up being published; there’s never a guarantee—would probably land in historical fiction again, but it would land in historical fiction the way that Mason & Dixon is historical fiction. So it’s about John Peter Russell and his involvement with the impressionists and post-impressionists in France. He was a guy from Sydney who went to France at the end of the nineteenth century with Tom Roberts, who would eventually come back to Australia and become Australia’s national painter. [Unlike Roberts], Russell stayed in France and befriended Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, and Cézanne and Rodin, and got really involved in those painters’ lives. It’s about how they all interacted, in the way that Mason & Dixon is ultimately about a friendship, or a strange relationship, or an offbeat relationship between two guys. It’s in that vein and also in a kind of hyperbolic style; it’s not a realist take on this situation at all. And what interests me about Russell is that… he apparently burned a lot of his art—and there were pieces that he didn’t consider to be finished until they were destroyed, [as if that act of destruction] was the culmination of what he was trying to do. So [the novel is] about an artistic mindset that sees destruction as part of the creative process, and how that inflects these friendships between guys who are all embarked on a on a creative process that has very destructive elements.

A few months after that discussion, when I spoke to Jaimie Batchan and Lochlan Bloom on Unsound Methods, I estimated that the novel was “probably a quarter written in draft form.” At that rate of progress—a quarter done in approximately one year—I would’ve had a projected completion period of summer 2025. That turned out to be right on-target, although I forgot about it in the interim and got over-optimistic with some new forecasts. At the end of 2022, I remember telling my father that I hoped to have a full draft by the summer of 2023. When I met with Ben again at the end of 2023, I’d only just finished the first full rough draft. Ben said he knew I was “deep in the depths of writing something” and he asked me for a timeframe. Here’s what I said:

When you can expect to see something, I don’t know. It’s always speculative and I hope my editor likes what I’m writing, but you never know. Yeah, I’ve got a full draft of a novel… and I’m working through it at the moment to revise it. I hope to have that done in the next couple of months, probably by the end of the northern hemisphere winter.

Far from finishing work on The Burning by the onset of spring 2024, I didn’t get a chance to hunker down with the manuscript until the dying days of the following summer. And then the really fine-grained edits, line by line, word by word, demanded another year of my time. So it goes.

Anyway, here I am—September 2025—having finished a first full draft at the end of August. If my fluctuating estimates of completion are, in retrospect, a little embarrassing, I’m less embarrassed and more surprised by the constancy of my vision between those early discussions and now. Here’s how I described the novel’s structure and style on Unsound Methods:

It’s broken into four parts, and then each of those four parts is broken down in different ways. The book is a historical novel, in a way; it’s about one strand of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. It’s set in France, but also in Australia, and also a bit here in Britain. What I wanted to do is, for each of the smaller chapters within one section, [I wanted] the sentences to represent the different artistic processes of the people who are in the chapter. So, for example, the second section of the book is alternating locations between France and Australia, and the French chapters are artists who are working with oils and canvas and watercolours outside, and the Australian chapters are more [focused on] an artist in training who begins with graphite, goes on to ink and etching [and] charcoal. So the notes that I have in the notebook for each of those chapters are about the sentence structure of the chapter. So, when you’re doing drypoint etching, you have a needle and you have a plate and you are engraving into [the plate], and then you’re going to slather it with ink, put a piece of paper on top and a print is going to come out. You’re moving with short but very precise movements of the hand, right? So the sentences in that chapter are going to reflect [that process]: they’re going to be short, intense sentences, probably a bit repetitious because an artist is etching the same lines again and again. Whereas, with chapters where watercolours are happening, it’s going to be splashier, it’s going to be much more colourful, there’s going to be a different diction because it’s not a monochrome process. So all those, I’ve broken down. [As for] what happens in [each] chapter, I have very vague ideas about [that] except for who is involved. So I would have a list of characters: “these people are here.” But [the notes are] more about the techniques that they’re using, what they’re doing and how that [action] relates to how the sentences are going to be made when I come to write that chapter.1

That description of part of the novel from three years ago remains true, even now that the novel is complete. So does this assessment of the things the final half of the novel would explore, as I described it to Ben two years ago:

There’s this sort of generational passing of impressionism into post-impressionism [from Manet to Monet to Matisse] with Russell as the crux of it, in a way. And it’s just striking to me, especially as someone who’s from Australia but lives abroad, to find someone who also has that sort of dedicated expat experience and a connection to a different landscape and a different place. So I’m kind of trying to write into that a bit and figure out why. Why did this guy who grew up in the Balmain area and across the northern beaches—why was it these cliffs on the west coast of an island to the west of France, why did he root his life there? … [And the] book is kind of about the relationships, the friendships between these people when they have profound divergences in the way they see the world and what it means to be creative in the world. So it’s also about Russell and Roberts having that relationship at a distance: one who’s committed to Australia as it’s becoming a nation, and to representing that, and one who is just totally about the individual experience at a specific moment in time in a specific place, completely unconnected from politics.

But aside from the “aboutness” of The Burning, what I wanted to get at here, today, was something about the internal vacancy I feel in the novel’s wake. When I speak of it in spatial terms, I do so cautiously but with certainty. The vacancy is something I feel deep in my body and, as above, it has a real sense of dimensionality to it. That dimensionality has been part of my experience of drafting the novel from the very beginning: indeed, the dimensions of the vacant space are, for me, the dimensions of work that now exists in the world. This is to say that I tend not to see myself as writing a story into being, so much as I see myself writing a shape. I tried to say this on Unsound Methods:

I was listening to you guys talking to Gabriel Josipovici a while ago, and I’ve heard him say this on a few occasions and it’s something that I agree with: which is that the origins of the work begin with a feeling of a shape. I think that’s the way he puts it. You have a sense in your bones, or in your body, that you’re carrying something around, and it has a certain shape—and it’s not a shape that you can draw—but you can feel that there are multiple components, and a proportion of time or volume between the arrival of different components and their integration. … So when I’m talking about a novel and planning a novel, what I’m trying to say is that there is a shape with these components that I can sense in myself and I know it’s a longer work because I know there has to be a delay and then a point of arrival for each component… So I know that there has to be some stretching of time in between each one, and that means length…

And I tried to explain something similar to Ben on Beyond the Zero:

But, you know, one of the most valuable and most influential things that I’ve ever heard came from the Canadian novelist and essayist Douglas Glover, who I worked with very briefly and have learned a lot from as a writer and reader. He said that when you’re reading a book, the first thing you need to do, if you are reading for structure and style, is to actually know how big this is. What is the size of this thing? What are its proportions? How is it broken down, purely in terms of number of pages? Where are the breaks, and where is each break relative to all the other breaks? How many pieces is it chopped into? How thin or thick is each one? And so on… For me, it’s a question of—I think of books as kind of time capsules. Each book—I can tell how much time it’s going to take based on the number of pages, and I want to know how much time [each unit of the book is] going to take up, relative to all the other units. … [I]t’s like feeling the time of the book: I can hold the time of it in my hand…

With At the Edge of the Solid World, I felt a tripartite shape. Its last two divisions shared the same dimensions, occupying the same amount of space—quadruple the space of the first part. That’s how I ended up with an opening stretch of prose, about fifty pages in length, followed by two equal parts of two hundred pages each. That’s how the first of those two latter parts came to be a four-stage rearticulation of the concerns of the first part, and also how the second of the two latter parts took the same form but was also—by virtue of simple sequentiality—in conversation with the preceding part, both extending it and revising its meaning for the reader. And the subdivisions of the subdivisions of those two divisions (each division being subdivided into four, and each subdivision again being subdivided into four) were, in some sense, a response to the rhythms of the murmur—the voice of the novel—as I sought to infuse the novel with silences, allowing it to catch its breath.

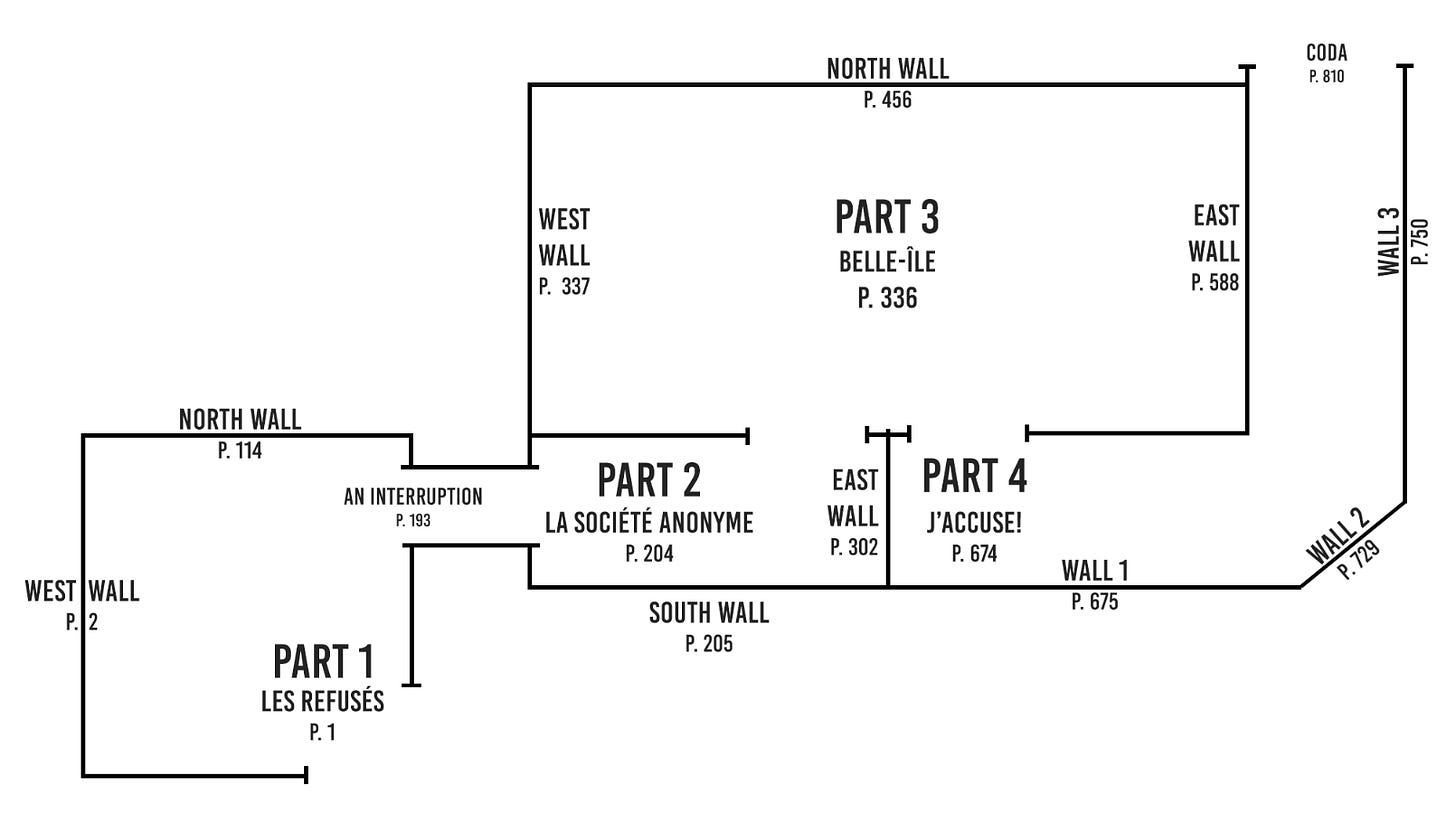

From the outset, I knew that The Burning would be more complex. Early on in the process, I began picking up on greater sonic variation in the murmur—my notes on prose style, above, are an early expression of that—and so I felt that it would be a more modular novel than the last one, with less symmetry to its divisions. Ultimately, it’s divided into four main parts with three shorter sections throughout: one to open, one to close, and one to dig a tunnel through time that connects the first and second parts. And these four parts are again subdivided, and the subdivisions are themselves subdivided, and—well—basically, I realised that this novel about art, and about many artists making art, wanted to have the shape of a full-blown art gallery. So here’s a glimpse at my not-so-great but at least serviceable mock-up of its structure:

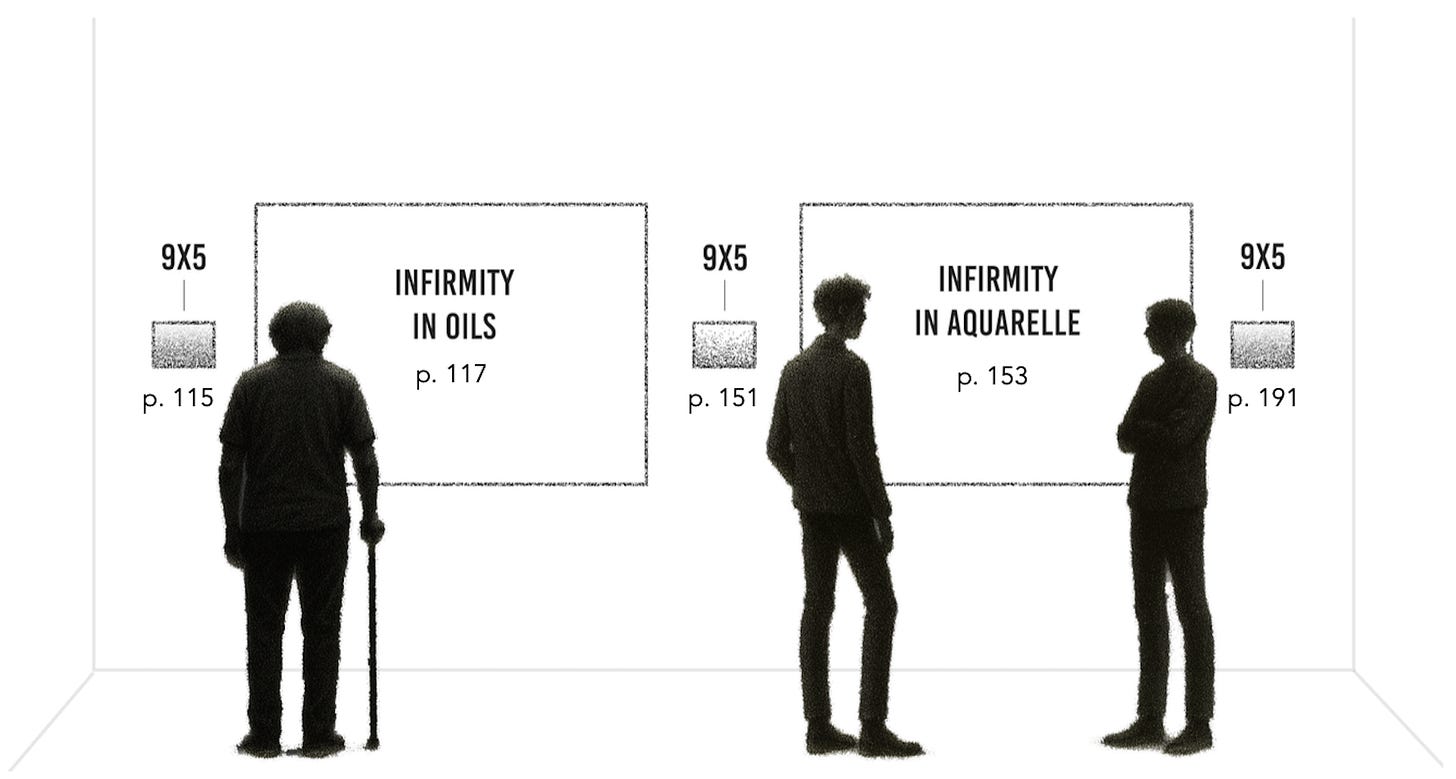

And, if you look closely at the gallery map, you’ll see that there’s a way of moving through the space: to the west wall of the first room, then to the north wall, then through the corridor (‘An Interruption’) to the next room, passing by the long south wall and turning at the east wall—and so on. So each wall marks a sectional subdivision, and the chapters within that section correspond to the works of art on that wall. Here’s an example:

Of course, if there’s any progression from manuscript to print proofs, I don’t really expect my hastily-drawn human forms to survive. But I’m hoping that something will go into those spaces to illustrate the relative proportionality of one chapter to the chapters around it, because I do want to signal the rhythm of the narrative—the rhythm imposed on the narrative by the structure—and thus the way time flows and pools throughout the novel.

In any case, there they are, externalised and made visible: “the dimensions of the emptiness that occupies the vacant space inside me where the work-in-progress used to be.” Ideally, eventually, that vacant space will give rise to a new work that will have a distinct shape of its own. For the time being, that’s the shape of the thing I’m no longer carrying around: my tribute—shrine? cathedral?—to the memory of John Peter Russell, and my own bid for an achievement in my chosen form of art.

My notes on stylistic variations look a bit like this, to choose random examples:

Begin with a rhetorical question:

(a) Did he know, when he did X, that he/it would…? [Explain…]

(b) How could he/how often would he… [attempt to do X]? [Itemise obstacles…]In tripartite situations, begin with uncertainty that ends in the POV character: “Whether X, when Y did such-and-such, would/did react in such-and-such a way [or knew…], Z could not be certain…”

Try to avoid using the copula as follows:

(a) Replace with colon, so “X was twenty-two…” —> “X: twenty-two…”

(b) Elide it altogether, so “Two years he’d been away…” —> “Two years away…”